They say an athlete dies twice. Well in my work and research I have had the pleasure to sit down with Olympic Champions, World record-holders and professionals from a host of sports around the globe.

I have built a four-pillar transition model based on my findings from research which suggest that Planning, Support Structure, Education and identity are key. Where my approach differs is that I feel all of these areas should be addressed in the formative years of an athlete not in the year after they retire.

For most athletes a major psychological obstacle is the fact that they have devoted their lives to a common task be it winning Olympic Gold, running faster, jumping longer, tackling harder, scoring more to the detriment of education, socialization or career planning.

But most importantly when a retired athlete is asked the question ‘Who am I?’ almost inevitably his/her response is to say ‘ I used to be a Rugby player/sprinter/footballer/rower etc. The danger for all of us in our lives is when we are defined by what we do for a living.

I was at a meeting this week with a company who want to improve their approach to performance. Society is beginning to recognise that wellbeing, mental health and performance output are inextricably linked. Research (and common sense) tells us that you are far more likely to deliver a clear-headed, quality performance if you are in a good space mentally. A key aspect of this is understanding how who you are affects what you do.

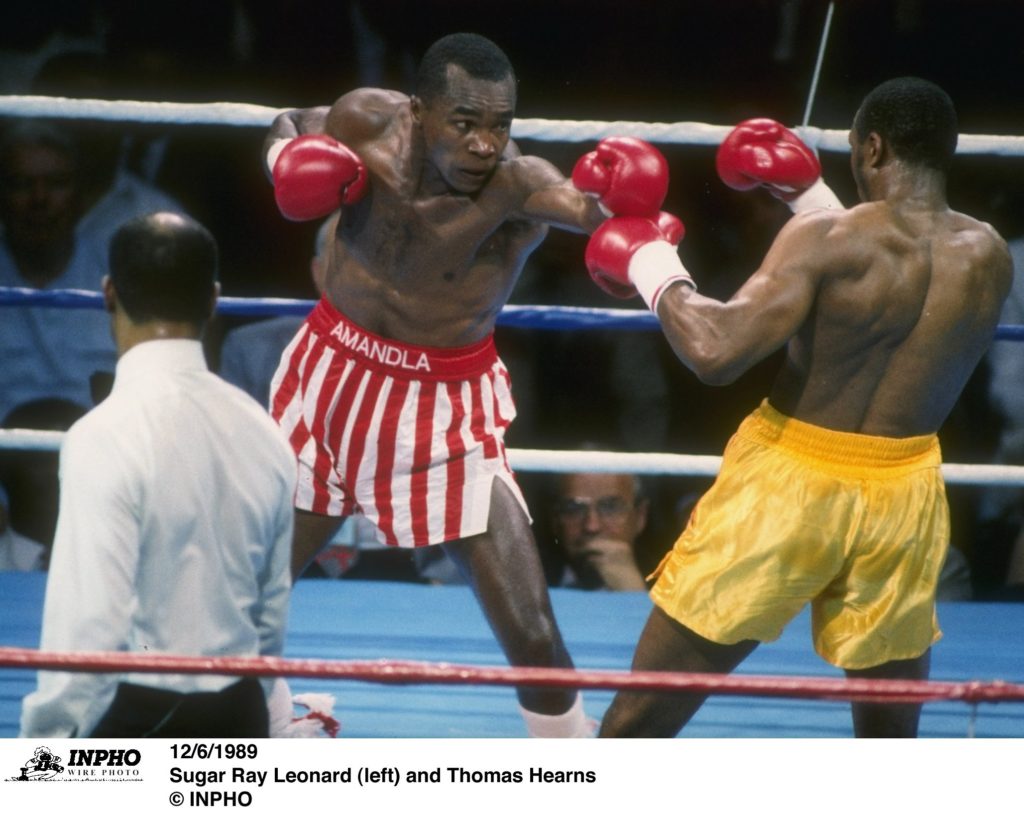

Going back to athletes in transition. The challenge is that when it ends the bubble they have lived in bursts and in the words of Sugar Ray Leonard suddenly ‘life happens’.

In the main athletes are ill-prepared for this. Gearoid Towey, former Irish Olympic Rower formed a company in Australia called Crossing the Line Sports where he champions mental health, wellbeing and transition planning for athletes. This is fast becoming a concept that the corporate world is embracing.

In a conversation with a British two time Olympic Rowing champion I learned that “it’s not the competition or the adrenaline I miss, it’s the simplicity of life”.

This same athlete spoke to me about how he didn’t feel he had any skills to offer any prospective employer. Here is a guy who rowed in the Cambridge/ Oxford boat race, won gold at two Olympics Games and yet he couldn’t see what traits an employer might see in him. He spoke of going to job interviews where the panel were excited to speak of his athletic achievements but then would inform him that they had no position for him.

I introduced him to an article in Forbes magazine about the ‘5 traits of the ideal employee’ and we spoke of the way he could interpret his career from a business perspective.

I asked him if in his career he could showcase periods of leadership, being goal-oriented, being self-motivated, seeing tasks out to the end etc. He is an exceptionally bright, charming guy and he figured out his path pretty quickly but it left me thinking how many other athletes feel the same way? Why does what they do become divorced from who they are?

It fascinates me why someone who can achieve so much in their sporting careers should see so little value in their athletic endeavours once they finish.

One of the simple tasks I set those I work with is to review the aforementioned article in Forbes magazine. I then ask the athletes to write down how this relates to who they are and outline where their career experiences can be relatable in the real world. This is a very simple tool but is remarkably powerful as most athletes at the elite level are not encouraged to consider anything except their performance goals throughout their career.

As one coach put it to me (in slightly more colourful language)

“I don’t care if they play with xbox all day as long as they perform when I ask them too”.

New Zealand Rugby recognized after the 2007 World Cup that Physical development of their players wasn’t going to solely bring them success. Strength and Conditioning science was such that every one of their competitors were similarly building bigger, faster, stronger athletes too.

“Better People, make Better All Blacks”.

New Zealand Head Coach Graham Henry and mental skills coach Gilbert Enoka, 2007.

They started working on programs to develop wellbeing and emotional maturity in their players. They didn’t just want to be the best physically, tactically and technically they also wanted to be the best decision-makers. Being better emotionally was key to them winning back to back World Cups. The next step was for guys like Rob Nichol and David Gibson at the New Zealand Rugby Players Association to start building programs and exit strategies for their members.

A network called ‘The Rugby Club” was set up to assist players in finding work once the ‘music had stopped’. All of this is about identifying that someday your career will end and understanding who you are will assist you in identifying transferable skills. Pretty much a lesson for all of us.

I had the pleasure to speak with Anthony Foley shortly before he passed away. He surprised me in speaking about his one career regret was not going abroad for a couple of years to experience a different culture. I had always seen Axel as a Munster man through and through which he was but we characterise our heroes as being one dimensional. Why shouldn’t he have had a desire to play rugby in a place like France.

There is a lot of talk at the moment in the aftermath of Simon Zebo’s return to Thomond park that the Irish management should offer him a contract back in Ireland. All the pundits seemed to think this weekend that it was a no brainer to get him back.

The one thing no one mentioned in all the coverage was whether the man himself wants to come home. Yes playing for Munster must be a special feeling for a player but his wife is French, his kids are learning a new language in a better climate and he is living Paris. Maybe he wants to develop skills outside of Rugby.

The thing that came to mind was Axel’s words about not knowing the friends he grew up with anymore. That his closest friends were still in the bubble. He spoke of the struggles some of his teammates had experienced.

He knew that former members of the squad were struggling with depression and other issues relating to the loss of identity. He felt privileged to be the coach of the club he loved but there was that sense of a little bit of regret for the man, not the rugby hero. This is a common experience for most athletes I have interviewed across the globe.

I get frustrated when governing bodies speak of providing assistance to athletes once their careers are ended. For me the key to producing athletes who are better prepared for transition is to create more rounded individuals who understand that sport just happens to be something they are good at right now but there is a world happening outside.

I am not suggesting that athletes are helpless in all of this and need to be treated like children. Quite the opposite in fact, I am saying sport needs to start building programs which give them the tools to take control of their lives and contribute in other ways once the athletic stage of their careers ends. This scenario is also applicable to all of us in our everyday lives.

Every one of us experiences stress and distraction in our lives. It is how we manage that that defines our success. Building career performance plans have to include your emotional resilience. The next time you are preparing for a job interview or a difficult conversation in work considers that a two-time Olympic champion and a Rugby legend shared the same doubts you do.

Go be a champion too.